This is a reblog from Bloomberg.com:

Bonnie Ross is in charge of Microsoft’s biggest video game ever.

By Joshua Brustein | October 22, 2015

Photographer: Michael Friberg for Bloomberg Businessweek

The women’s volleyball locker room at the University of Southern California’s 10,000-seat Galen Center isn’t the most glamorous green room, but Bonnie Ross couldn’t care less. It’s June 15, and in 30 minutes, Ross, who’s in charge of Microsoft’s most valuable gaming franchise, will take center stage at the industry’s most important conference, E3. It’s the pitch of her career—a preview of Halo 5: Guardians, set to go on sale on Oct. 27.

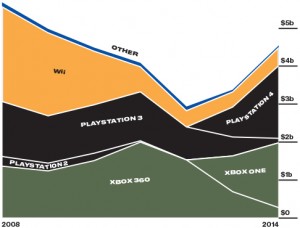

Three years in the making, Halo 5 is widely anticipated to be one of the biggest game releases of 2015. Ross, 48, runs 343 Industries, a studio within Microsoft. She manages 600 people and has likely overseen the spending of more than $100 million for Halo 5 alone, which is typical for a release of this size. (Microsoft declines to give an exact figure.) It’s a huge production—and a chance for Microsoft to recoup its investment in Xbox One, which has lagged behind Sony’s PlayStation 4.

The fate of the Xbox has been linked to Halo since both debuted in 2001; Microsoft executives at the time said the platform probably would have failed had Halo not been such a smash. Fourteen years later, Ross still describes the game as a way to prove how good the Xbox itself is. “Halo is all about innovation and pushing our technology,” she says. “We feel like we’re pushing where we need to be, and pushing Halo.”

Five-foot-6, with long brown hair and an easy smile, Ross is athletic and direct, and betrays no trace of the awkward intensity common among engineers. Nor does she wear the kooky fan-themed T-shirts that are the standard outfit of most game developers. At E3 she has on a leather jacket, jeans, and black leather boots. If she’s nervous, she’s covering well, staying upbeat. Still, she jerks to attention when Terry Myerson enters. “Sorry,” Ross tells me, excusing herself. “My boss just showed up.” Myerson, a Microsoft executive vice president, is in fact Ross’s boss’s boss. Their boss’s boss, Chief Executive Officer Satya Nadella, is waiting in a seat in the audience. He’s the first Microsoft CEO to attend the show in eight years. Even for one of the world’s largest companies, there’s a lot depending on this one game.

Halo’s influence is broad. Over the last 14 years, consumers have spent $4.6 billion on Halo products, about 25 percent of that on nongame merchandise. Microsoft has licensed the name to everything from special editions of Monopoly to a full body-armor suit that sold for more than $450. The first Halo book, a novel called Halo: The Fall of Reach, was actually published before the first game was released. For a time it looked like Peter Jackson, the director of The Lord of the Rings, might make a Halo movie. There’s now a Steven Spielberg television show in the works for Showtime.

When asked about her ambitions for Halo, Ross always comes back to Star Wars, which she adored as a kid. “For those of us that are a little bit older, we saw Star Wars and stood in line the first time around,” she says. “We are seeing the same thing with Halo, where a lot of dads and parents that started playing when they were 20 or 30 now have kids that are coming in through our, you know, Mega Bloks line.”

When asked about her ambitions for Halo, Ross always comes back to Star Wars, which she adored as a kid. “For those of us that are a little bit older, we saw Star Wars and stood in line the first time around,” she says. “We are seeing the same thing with Halo, where a lot of dads and parents that started playing when they were 20 or 30 now have kids that are coming in through our, you know, Mega Bloks line.”

In the Lady Trojans locker room, Ross chats with several leaders of 343, among them Frank O’Connor, the franchise development director; Josh Holmes, the head of Halo’s internal development; and Tim Longo, 343’s creative director. It’s a wonder they’re all standing. Ross and her team have spent the previous 17 days fixing 700 software bugs in a “sprint,” as programmers call the race to meet a deadline. In one case, a flying armored man had gotten loose in the code and was floating around unmoored, liable to appear anywhere, even during a serious firefight. In another, someone in the art department had thoughtlessly stuck a rock in the path of a plane in a narrative scene. More disturbingly, the plane would fly right through it.

Excited by the Xbox One’s processing power, animators decided to build a fully interactive cactus that could move in different ways depending on where a gamer shot it. They blanketed one level with cactuses all the way to the virtual horizon. Even the new turbocharged Xbox couldn’t render the needles fast enough. At one point during the development process, the cactuses were the single biggest contributor to technical problems. Finally, the developers convinced the artists they had to go. Says Chris Lee, 343’s director of production: “There were hard feelings on different sides for about a month from the cactus fallout.”

Finishing the coding sprint, saving Microsoft’s console—all of this is top of mind as Ross strides to the stage, smiles, and waves. It’s a friendly crowd. “Let’s start tonight with the first Halo game—” she begins, but she’s immediately drowned out by applause. “Thank you! That’s right—that’s where I want to hear the applause,” says Ross, before finishing her sentence: “—the first Halo game built from the ground up for Xbox One, and the game that fulfills both the promise of the Halo universe and the power of Xbox One.” Ross settles into her pitch. “Master Chief, hero or traitor?” she asks. “Spartan Locke, friend or foe? Epic worlds, epic battles, epic scale!”

The lights go down, and a trailer booms to life on a 50-foot-by-28-foot screen. A cyborg trains his assault rifle into the distance, and a fleet of spaceships flies over an alien landscape. A gravelly voice announces that Master Chief, the hero of the Halo epic, has gone absent without leave. Ross quietly disappears from the stage, as her deputies scan Twitter’s reaction on their Windows phones. A few hours later, she meets Holmes and O’Connor for lunch at a nearby steakhouse. They’re relaxed, elated, for one afternoon at least. The Twitterverse is pumped.

Bonnie Ross is a video game executive by happenstance. She was a good volleyball player in high school, but her father insisted she pass up athletic scholarships to focus on something useful. So she studied technical communications and computer science at Colorado State University, which led to an internship at IBM. She graduated, then applied to work at NeXT, Apple, and Microsoft; her first two choices never called back.

Ross started at Microsoft in 1989 but quickly got bored. She liked drawing a paycheck but had a normal human’s lack of enthusiasm for drafting manuals. “I just wanted to take a break, just for, like, one year, to work on something that my friends would understand,” she says. She talked her way onto a team developing a basketball game for Microsoft’s nascent video game business.

Ross knew more about sports than gaming. Titles she worked on, first for the PC and then the Xbox, included a collection of simple games called Fuzion Frenzy that came out with the original Xbox console. She managed a string of games before choosing to focus on Halo in 2007.

“If I take it over, I want to be George Lucas. I want to own everything”

Microsoft had bought Bungie, the studio that created Halo, in 2000. For the most part, it left the studio alone, but for creative reasons, Bungie wanted to spin off. In 2007, Microsoft let the company go, keeping Halo and forming 343 to run it. Bungie now makes the video game Destiny, a key Halo competitor.

Ross’s colleagues saw her decision to take on this project as a bad move for a young person on the rise—there was a feeling at Microsoft that Halo had run its course. “People felt like, Let’s get another Halo or two out, and it’s the end of the franchise,” Ross says. “The thing I asked for was: If I take it over, I want to be George Lucas. I want to own everything, and I want to do things differently.”

The video game world, dark and conspiracy-prone in the best of times, worried that Microsoft would kill the game with corporate-think. O’Connor, then at Bungie, helped with the transition. He went into his first meeting with Ross expecting a suit looking to check off the boxes. “Bonnie came in and really surprised everyone,” he says, “because she’d read all the novels, she was deeply immersed in the fiction, and she’d played all the games.” He quit Bungie and returned to Microsoft to help her with the new studio, which they named 343 Industries after a villainous piece of artificial intelligence that shows up in several Halo games.

Each new hire at 343 puts a head shot on the wall to help colleagues keep track. Photographer: Ian Allen for Bloomberg Businessweek

The 343 team moved into Bungie’s old building, a former True Value Hardware store in the Seattle suburb of Kirkland, near Microsoft’s headquarters in Redmond. The building is perfect for coding. It has an open floor plan and little natural light. “During game development, you can feel the pulse,” Ross says. “You can walk in and tell if we’re off or not, and whether morale is up or down, because we all act as one.” There’s a kitchen with vending machines and free soda, a basketball court out back, and long lunch tables well-suited for playing the fantasy card game Magic: The Gathering.

The headquarters can hold only about 230 people, so more than half of 343’s employees are in another building down the block. Ross spends a lot of time shuttling up and down the hill between the two. On her way to the satellite building one day this summer, she tells the story of founding a studio from scratch after almost every developer from Bungie quit. “It was just me and the consumer-product guys,” she recalls, as we pass two young men in their obscure T-shirts. Ross smiles and says hello. After they pass, she admits to not knowing who they are. When she shops in a nearby grocery store, Ross says, she just smiles and greets anyone who seems to be the right age to build video games for a living. She figures she’s probably their boss.

While many of the people Ross oversees are computer programmers or designers, the roster at 343 also includes cloud-computing experts, a professional team of competitive video game players, and a psychologist focused on user interfaces. There’s a group working only on sound; most of the noises in the game are custom. Engineers trekked to a gun range in Bakersfield, Calif., to record bullets whistling past their ears. They went to a concert hall in Prague to get a proper angelic chorus for the big moments. They visited a hot spring in Iceland to get ambient sounds that seemed extraterrestrial.

Ross spends a lot of time in dim conference rooms—good for playing video games—as employees shuffle in for meetings. Her third appointment one day in late September is with the consumer-products team. Ross is a gamer, but she also really cares about all the other stuff 343 makes. A half-dozen people come in, bearing toys. She surveys their offerings and immediately grabs a 2-foot-tall Master Chief statuette, plopping it into the seat next to her. Ross then starts grilling an underling about another line of products. (As a condition of attending the meeting, I had to assure Microsoft that I wouldn’t discuss the toys coming out next year.) “There are no manufacturing shortages?” she asks. “As of today, yes,” he responds. “Is that a confident yes?” she asks. He stutters a bit, but assures her that yes, he’s confident.

On another visit, Ross shows off a Halo-themed clutch. It’s an army-green bag, designed possibly for the sophisticated woman who wants to signal her loyalty to Xbox during a night out at the theater. Ross laughs about it, admitting there’s really no chance it will be a big seller. But she can’t resist.

Her affection for the clutch is more than whimsy. As a rare female executive in an industry dominated by men, Ross worked to remind her colleagues that girls play video games, too. She’s insisted that fully realized female characters play prominent roles in Halo 5 and made sure that dorky Halo T-shirts come in cuts for women, too. This may seem unobjectionable, but in the world of video games, trying to broaden the audience is daring. For the past year or so, Internet trolls have mercilessly harassed women in the gaming industry. A Microsoft press officer asked me to omit any personal information about Ross to protect her from “doxxing”—a favorite tool of online harassers—in which personal information, including addresses and names of children, is widely distributed. (He later relented.)

Her affection for the clutch is more than whimsy. As a rare female executive in an industry dominated by men, Ross worked to remind her colleagues that girls play video games, too. She’s insisted that fully realized female characters play prominent roles in Halo 5 and made sure that dorky Halo T-shirts come in cuts for women, too. This may seem unobjectionable, but in the world of video games, trying to broaden the audience is daring. For the past year or so, Internet trolls have mercilessly harassed women in the gaming industry. A Microsoft press officer asked me to omit any personal information about Ross to protect her from “doxxing”—a favorite tool of online harassers—in which personal information, including addresses and names of children, is widely distributed. (He later relented.)

More mundanely, Ross knows there’s a risk in clogging the aisles of Toys “R” Us and Walmart with anything that Microsoft can stamp Halo on, whether it’s a clutch or a squirt gun. She says that when she inherited the game, the philosophy was to say yes to any company willing to pay royalties. The worst? Some tacky pajama pants. “The pajamas actually were really comfortable,” Ross says. “But they weren’t super high-quality.” When she took over, she cut the line.

At one point she meets with O’Connor to talk about what they both refer to, grandiosely, as the Halo Canon. O’Connor is a cue-ball-headed 45-year-old whose voice still has a hint of a lilt from his native Scotland. He’s in charge of Halo’s fiction business. Almost 20 Halo novels have been published, and a dozen have been New York Times best-sellers.

O’Connor had a bit role in the Web series Halo 4: Forward Unto Dawn, and even writes Halo-themed fiction himself, most recently Saint’s Testimony, a digital-only short story. He’s in charge of the Halo Story Bible, the written record of everything in the Halo universe. It details every character, weapon, and plot development in the Halo world. Printed, it runs to more than 1,000 pages.

The tale, which begins about 500 years from now, is confusing as hell. Humans have spread to hundreds of other planets and civil war looms. To quell the rebellion, the United Nations Space Command builds a series of superhuman warriors, which they dub the Spartans. Then aliens attack. That’s where the first game starts, with players taking on the role of Master Chief. The story of each subsequent novel, spinoff game, and iPhone app has to pass muster with O’Connor’s team. In her meeting with O’Connor, Ross discusses a line of Halo short stories. “I like the digital shorts, because they’re like adult comic books,” says Ross, who’s a little annoyed they haven’t had a best-seller lately.

O’Connor says perhaps a studio with a multibillion-dollar product shouldn’t worry too much about the mainstream acceptance of its novelistic stylings. “There’s no money in it. The investment is in awareness,” he says.

“It’s world-building!” Ross says.

In late July, Longo, 343’s creative director, grabs a controller and sits down in front of a small television, navigating Spartan Locke through a watery part of a planet in the middle of an alien civil war. The view on his TV is mirrored on a large pull-down screen, so a group gathered around a nearby conference table can analyze the game, usually by yelling. There’s a lot to yell about. The water doesn’t splash convincingly. It’s as if Locke’s legs just disappear into a sheet of glass. Then Longo aims his rifle at a few aliens and pulls the trigger. He moves on to the next group of enemies, but everyone else in the room is making noise about the corpses he’s leaving behind. “Guys are jittering on the ground for a long time after they’re dead. There’s something weird going on,” someone chimes in. One employee jots down notes. Every day this summer, similar meetings are taking place in both 343 buildings.

Guest players are welcome. Once, Richard Sherman, star cornerback of the Seattle Seahawks, showed up at the office to engage in multiplayer combat. Ross is a big sports fan, and the Seahawks have an open invitation to play against her in-house gamers. The jocks fare no better with controllers in hand than the gamers would if they strapped on shoulder pads, which amuses the Seahawks to no end. “They kept getting zero, and they loved it,” O’Connor says.

In Halo 5, after Master Chief goes AWOL, he’s pursued by another group of Spartans. Ross and her team chose this plot not only for whatever literary appeal it might have, but also to show off the processing power of the Xbox One and Microsoft’s cloud servers. Halo 5 adds six new playable characters, who can be controlled individually and cooperate in real time. A multiplayer mode called Warzone allows 24 people to compete simultaneously.

Getting multiplayer gaming right has become a sore point for 343. In November 2014 the studio released Halo: Master Chief Collection, a single disc for the new console with remastered versions of the first four games. It was a clever way to let Halo fans play on the new Xbox while squeezing some more money out of old games.

Ross, O’Connor, and others flew to Los Angeles to blow off steam at a launch party. As the event was going on, a few complaints began popping up on social media from gamers in Australia and New Zealand who weren’t able to find people to play against in online matches. This didn’t seem like any reason to leave a party. “There’s never enough population there, I’m sure it’s nothing,” Ross remembers thinking. Data coming from Microsoft’s own servers wasn’t showing a problem.

That data was wrong. “By the time we got back from the event it was, like, 4 a.m., and things should have been running smoothly at that point,” O’Connor says. “They weren’t.” Players weren’t being matched up for online games, leaving a lot of frustrated customers. The problems stretched on for weeks, and Ross issued multiple public apologies. She winces when asked about what she calls the worst moment in her career. “We obviously had no idea we would fall down,” she says.

Play tests for Warzone take place in an overcrowded room that can hold only 18 consoles and screens, with 6 more jammed against a wall in the hallway. After leaving his victims twitching in one room, Longo heads over for another test. Over the course of the 30-minute event, more than half the players are locked out of the contest when their computers crash. Some players use the break in the action to lean over and start critiquing the play of a neighbor. One guy passes the time with a plastic cup of candy, a Mountain Dew, and his phone.

William Archbell, a senior software engineer at 343, has been running these tests for two years. He stands with arms crossed, watching. “Play test is fun, because it’s where you validate your ideas,” says Archbell, who’s tallish and has an ambitious beard. “People do weird stuff.” The same staffers squealing with delight turn hypercritical when they put down their controllers. “Speed freak didn’t feel fast at all. I expected speed,” one offers. “I grabbed the booster upgrade and couldn’t feel any difference,” another says.

When Archbell started, the game consisted of blocky graphics running at 10 frames per second. Now it’s blossomed into a dense, high-definition, beautifully rendered 60 frames per second. (Hollywood usually makes do with only 24.) He quietly gives a colleague a tip, but then admits he’s not as good at the game as he used to be. “I used to get to play more,” he says. “But now I’m in management.”

For games, fall is the blockbuster season. Electronic Arts is delivering a Star Wars game, and popular franchises Call of Duty and Fallout will have new installments. According to 343, Halo 5 is ahead of almost every game in terms of consumer awareness and “purchase intent,” trailing only Call of Duty by these measures.

Although each Halo launch has been larger than the one before, there are fewer Xbox Ones now than there were Xbox 360s when Halo 4 was released. That could depress sales. Before previous Halo launches, Microsoft executives confidently predicted the new game would be the biggest ever. Not this time.

Even if Halo 5 is a success, Microsoft may have waited too long. “Halo would have made a huge difference last Christmas. All the other franchises Microsoft has, with the exception of Minecraft, are very old, tired, and same-y,” says Gareth Sutcliffe, a consultant who worked at a Microsoft gaming studio until 2013. “Not having Halo for so long has really hurt the install rate and may have lost them the overall war.”

In the final weeks, game testing shifts to employees’ homes. Each weekend, the development team sets a time for people to log in and begin multiplayer versions of the game to simulate what will happen in the real world—and avoid the glitchy fate of the Master Chief Collection.

At a launch meeting in late September, one harried producer reports that the participation rate in the previous weekend’s play test was unexpectedly low. “Well, you know you scheduled it during the Seahawks game,” Ross says. The man seems momentarily stumped, as if he’d never considered that someone would watch football instead of playing video games.

Ross’s husband hadn’t been happy the previous weekend when she said she needed the TV during the football game. He’s not much for games, and generally leaves the room when she starts shooting virtual assault rifles at her colleagues from the couch. Ross considers herself a middling player and prefers playing at home to tests in the office, where the nimble-fingered young people she half-recognizes at the grocery store make quick work of her. She estimates that once the game goes live, she’ll be able to play online for a few weeks before the gaming public figures out all the tricks and becomes too good for her.

Ross has been tutoring one new Halo player: her 10-year-old son. Until recently, she’d considered the game a bit too violent for her children, but she’s begun letting her son play with her. “I firmly believe that your kids are going to play games, and you should play with them,” she says. “I want to share that first experience with him.” Mother and son have worked through two levels of Halo 5 together and occasionally play in multiplayer modes. She’s better than he is—for now.

“He basically blows himself up, and I’m like, ‘You can’t throw a grenade at a wall,’ ” Ross says. “But that’s where we are right now, and it’s a good point to be in.”

“I want to be George Lucas”. LOL

I have nothing against George Lucas but a substantial amount of the Star Wars community don’t really like his changes to the Star Wars universe even if he was the one who created most of it. As for Halo, we have already seen something of the sort for Halo 4 and 343i in general. Some Halo fans don’t really like them that much. Hopefully Halo 5 will bring Halo back.

She didn’t mean it like that. She meant the absolute control over the franchise. She has made some missteps. I do hope Halo 5 redeems not only her, but 343 as a whole. I really want to get past the HMCC.

Oh no I knew what she meant. I just found it humorous that they also shared another “connection”.